Evacuation modeling

Evacuating the occupants of a building effectively is critical to minimize casualties due to several natural or anthropogenic hazards. Building evacuation models can help us prepare for future emergency events and illuminate possible shortcomings of current evacuation designs. However, these types of models are seldom validated with real evacuations, which is a critical step in assessing their predictive capabilities. Therefore, we constructed an agent-based building evacuation model to simulate a real tsunami evacuation drill in a K-12 school with approximately 1500 children and staff in the city of Iquique, Chile (Poulos et al., 2018). Our results show a good agreement between the simulated and real evacuations, suggesting that these types of models can be used in emergency planning.

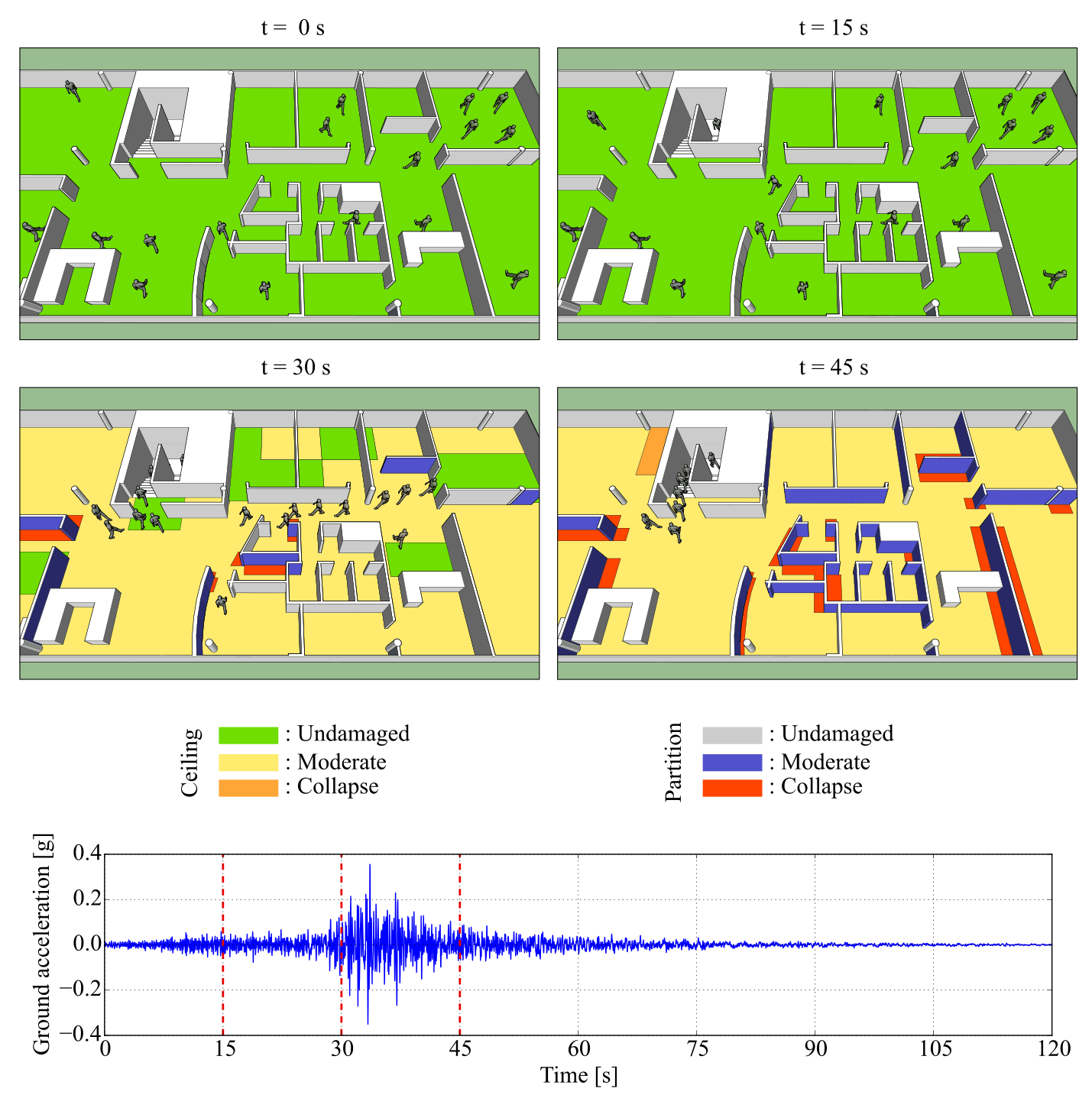

We then used the same model to simulate the effect of building damage due to an earthquake on the evacuation of a building. As a testbed, we used a four-story reinforced concrete frame building. We used the ground motion at the location of the building to compute the inelastic response of the structure, which we then used to estimate the damage to building contents (e.g., false ceilings and partition walls). We then coupled the building damage with the response of evacuating agents. Several simulations at different ground motion intensity levels were then integrated with the seismic hazard at the site to compute seismic risk. The results of this analysis were cast as probability distributions of variables that measure the system’s overall performance (e.g., evacuation times, number of injured people, and repair costs) for specific time windows.

Finally, we expanded the model to simulate city-scale evacuations considering people and cars (Castro et al., 2019). We used the model to simulate a tsunami evacuation of downtown Iquique during the same drill considered when simulating the evacuation of the K-12 school. The study area had 46,500 people and 2,000 cars evacuating to the safety zones shown in Figure 3. Running several simulations of the model, we estimated mean evacuation times reasonably close to those of the actual evacuation drill.